(Being my second post in response to Jane Hart’s 10 Tools Challenge 2013)

For business, the Internet means that a potential customer could receive your message almost anywhere. But although it’s getting better at it, the Internet can’t tell you exactly how to make your message intersect with its audience at the right time, place, and condition of readiness. It’s not quite the case that f(map) = territory, but it’s close enough that one quickly finds that there needs to be a triangulation layer over it: a set of tools that, taken together, increase your potential reach and return.

This is a big issue when your business more or less lives on the Internet like Versatile PhD. We provide a variety of resources to subscribing universities that help graduate students in many disciplines explore, identify, and prepare for careers outside of the typical academic faculty path. Great stuff. But a university campus is awash in information. We’re competing with an untold number of demands on the attention of our potential users. So we’re building a triangulation layer, using two tools that were familiar to me to feed into a brand-new one. Familiar: Twitter and Google Reader. New: Buffer.

We’re a small company with a far-flung client base. We have great partners on our client campuses (career centers, graduate schools, and provosts’ offices), but we don’t have access to their communication channels. And, like us, they have to prioritize a wide range of demands and efforts, so anything we can do that calls out to their campuses will help us both.

The facts cry out for a social media solution, really. It gets at the great number of unanswered questions present at the start. How do we interact with potential users? How do we draw and then keep their attention? How do we get them to participate with us in a shared space, or even take ideas from us and propagate them in new directions? And how to do this when there’s limited time?

VPhD’s first entry into social media preceded my arrival by less than a year. My boss, the founder and CEO, went with Twitter, not Facebook. She wanted a platform for participating in conversations about the state of the PhD rather than for marketing. We’ll get to Facebook at some point in the near future – we have our hands full with the discussions and forums on the site, and don’t need another content and curation demand just now. What we did need was a vehicle to start to give the business a voice.

At first, it was the voice of my boss. Her interactions were with friends, allies, and fellow-travelers in higher education circles, primarily, with occasional forays into the career space more broadly. But when I took up the assignment, I decided that I wanted to turn that voice more overtly toward our potential users: graduate students and PhDs.

But what to tweet? There’s no shortage of articles, blog posts, and other content about the state of the PhD and higher education. All kinds of social and economic trends are relevant to the labor market in higher education.

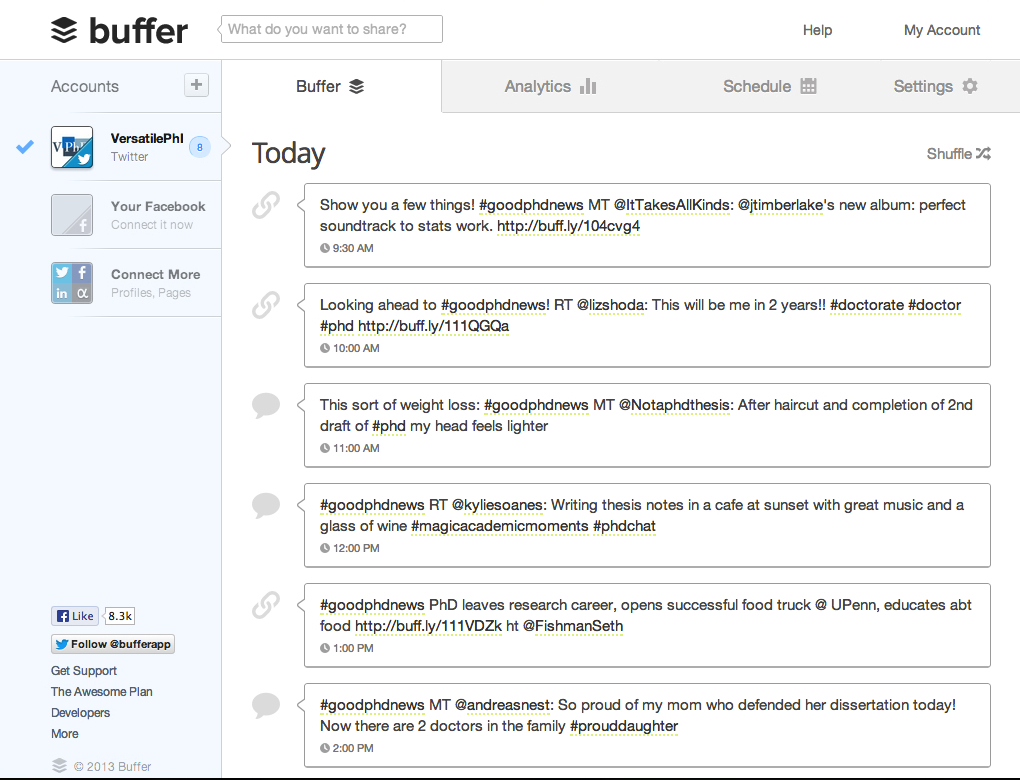

The niche, broadly speaking is good news about PhDs and the PhD itself. Or, in hashtag form: #goodphdnews. The idea came to me in mid-December, when I’d begun exploring ways to find Tweet-able things related to PhDs or the degree itself. Important milestones in the academic calendar happen then, so it wasn’t long before I started seeing good things:

From there, it was a short mental leap to something that people in my part of DC had been doing earlier in the year – #goodWard5news – which gave me a model for the new hashtag.

It seemed like a good way to engage with potential users of our resources who might not otherwise know about us, and turn @VersatilePhD into something a little more lively than a platform from which to post relevant articles and other material. Direct connection leads to attention and communication, so we hear. So borrowing a bit of the #FollowFriday spirit, at the end of every work week, @VersatilePhD tweets out the #goodphdnews all day long. So now we have something we didn’t before: a type of story to highlight, of good things happening to or created by people with PhDs or working on them.

Over the next month or so, I started putting a few more tools in place to streamline the process. From beginning to end, it entailed a lot of work: finding the best keywords and hashtags, coding good search queries, reviewing the search results, recrafting the best ones as #goodphdnews RTs or MTs, and then finally tweeting them. After a few rounds of doing everything almost manually (and discovering that PhD tweets are a regular target of tweet-plagiarizing fake accounts), I found a way to aggregate the tweets so that I could rapidly find those with potential, and picked an automation tool for the final act of tweeting itself: Buffer.

Buffer is browser-based and straightforward. The tabbed dashboard shows the three main functions: the stack of tweets you’ve set up to go out; analytics to track clicks and engagement with those tweets once you loose them on the world; and the scheduling function, which is the heart of it all.

It runs through the browser as an extension that adds a Buffer option to any tweet viewed at twitter.com (visible in the Twitter screenshots above, which I took recently) and other places. Click that link, and you get an editing window on the screen with the text of the tweet ready for quoting or editing. Share it right then, or “buffer” it for later.

Buffered tweets appear in the stack, and you can then drag and drop within the stack if you prefer a different order than the one in which you entered them. Links get rewritten with the buff.ly shortener, but otherwise it works more or less transparently. Rather than assigning each buffered piece of content a time, you set up a schedule and then arrange the content over it. That seemed a little curious at first, but I’ve grown accustomed to it.

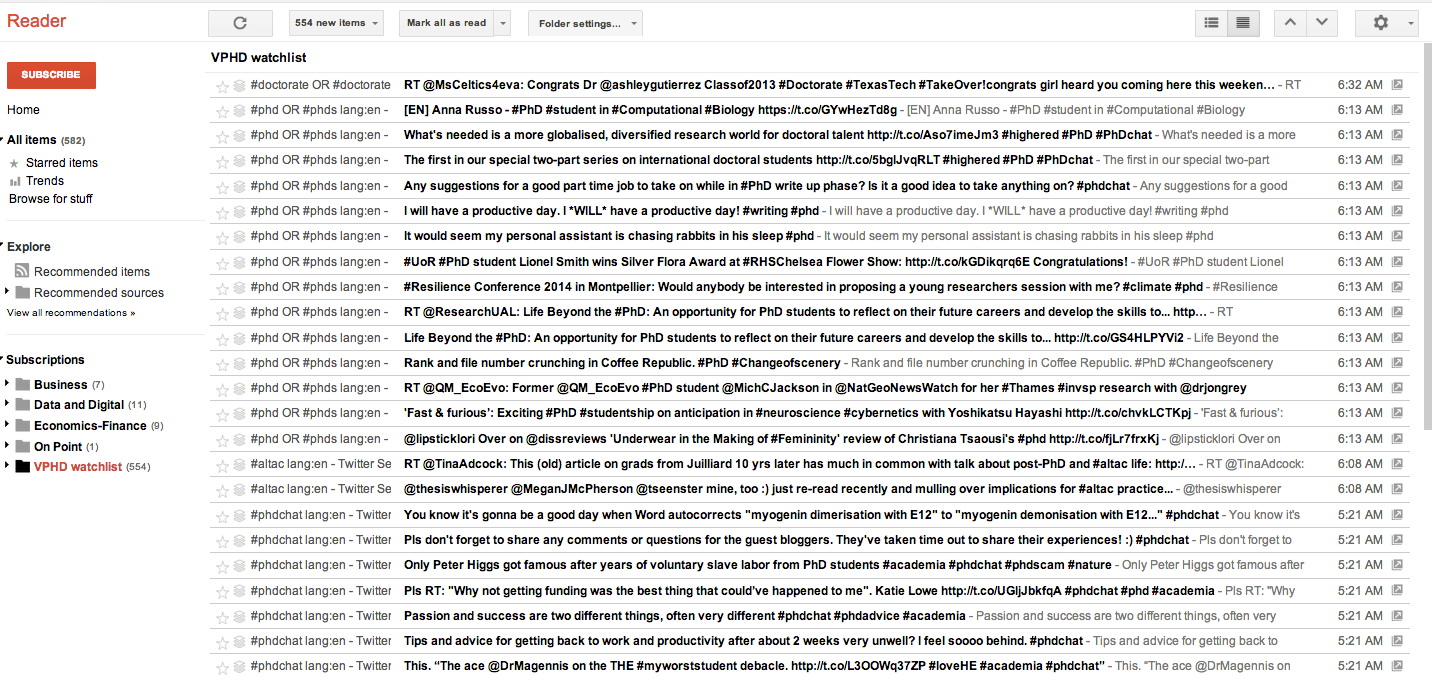

With the delivery mechanism in place, it wasn’t long before I also found a good aggregating mechanism: my dear and now soon-to-be-departed friend Google Reader. Once you realize that RSS will work on anything that can be expressed as a URL (` tweets), it’s a quick step to writing up a variety a queries that deliver an entire universe of tweets all at once.

(The sharp-eyed will notice that Buffer integrates with Reader, too.)

At this point, the #goodphdnews process is set, having just a few steps. Sign into Reader, Twitter, and Buffer. Scan the Reader stack, which shows just enough of a tweet for me to see whether it might be a good candidate. When I click through Reader into a tweet, if I want to recast it as #goodphdnews, Buffer lets me write it up instantly. It takes about an hour to scan a thousand tweets (finding the whole-cloth text of a tweet I’ve seen before indicates another fake account bot – they appear over and over again). Once I’m done, I add or subtract scheduled times for the buffered tweets to be shared. We only do this on Fridays, so the delivery happens more or less between 9am and 6pm Eastern.

Through this experience, I’ve found a number of themes and topics worth reflecting on as I continue. Social media is not a large part of my job, so finding ways to fit tools to the process makes it happen within the amount of time I can allot it. One is truly fortunate if one’s work is of a kind that presents interesting problems, and perhaps doubly so if the search for solutions actually results in something that works better and faster. Of course, it’s also true that any good problem or challenge tends to unfold into smaller problems or challenges as you work through it. In the worst case, this can lead to a sort of problem/solution cascade, where you never manage to get a good equilibrium. Wanting to connect with others in the same intellectual or business space is that kind of problem.

A complex problem will most often require multiple tools that add up to a satisfactory process or solution. Yet it also seems true that the urgency of business demands often mean that you never have the time to research a comprehensive solution, which means you’re going to end up using the tools that are closest to hand. Hopefully they’re also close enough to the desired result that they can help you triangulate toward a solution.

More to come as I continue through the 10 Tools Challenge over the rest of 2013.

–

Spalling is what happens when certain types of warheads strike armored fighting vehicles, too. Either the shock wave of the strike on the exterior is so great that the wall of the crew compartment breaks down suddenly and kinetically, flinging fragments throughout and wounding its crew or disabling its mechanisms, or the warhead pierces the armor in order to penetrate and itself produce the same effect.

Spalling is what happens when certain types of warheads strike armored fighting vehicles, too. Either the shock wave of the strike on the exterior is so great that the wall of the crew compartment breaks down suddenly and kinetically, flinging fragments throughout and wounding its crew or disabling its mechanisms, or the warhead pierces the armor in order to penetrate and itself produce the same effect.